Alexander «Skunder» Boghossian (22.07.1937 г., Аддис-Абеба, Эфиопия – 4.05.2003 г., Вашингтон, округ Колумбия) – самый знаменитый африканский художник.

Первый африканец, чьи работы выставлялись на европейских выставках. Первый эфиопский художник, чьи работы приобрели музеи современного искусства во Франции и США.

Большую коллекцию его картин в 1992 году приобрел Смитсоновский институт (англ. Smithsonian Institution)

Родился в семье богатого армянина Boghossian Kosrof Gorgorios и эфиопки Weizero Tsedale Wolde Tekle.

**

Alexander "Skunder" Boghossian was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1937.

When he was a child, his parents took seriously his talent and encouraged him to become an artist.

In 1954 when he was seventeen years old, Boghossian won second prize at the Jubilee Anniversary Celebration of Emperor Haile Selassie I. The next year he was awarded an Ethiopian government scholarship to study in Europe. He spent two years in London where he attended St. Martins School, Central School and the Slade School of Fine Art. He extended his sojourn in Europe another nine years as a student and teacher at the Academie de la Grnade Chaumiere in Paris, and as a student and teacher in the atelier of Alberto Giacometti.

In 1966 Boghossian returned to Ethiopia where he taught at the Fine Arts School in Addis Ababa until 1969. He made his first trip to the United States in 1970 and, except for a trip home when his father died in 1972, he spent the remainer of his life in the US. The 1974 revolution in Ethiopia prevented Boghossian from returning to Ethiopia. He has lived in the USA as a permanent resident, and artist in exile.

Throughout his career Boghossian has had a successful dual profession as an art instructor and artist.

In addition to teaching in France and Ethiopia, Boghossian has taught in the USA at Atlanta University, Hampton University, and Howard University, where he worked in the School of Fine Arts since 1974.

As a practicing artist, Boghossian's paintings have been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Ethiopia, the Caribbean, Europe, North and South America. He is also distinguished by being "the first Africa to..." He was, for example, the first contemporary African artist to have work purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and he was the first African commissioned by the World Federation of the United Nations Association to design a First Day Cover for a United Nations stamp. His pen and ink drawing for the cover and the accompanying stamp were on the theme of "Combat Racism." The date of issue was September 19, 1977.

Большую коллекцию его картин в 1992 году приобрел Смитсоновский институт (англ. Smithsonian Institution)

Родился в семье богатого армянина Boghossian Kosrof Gorgorios и эфиопки Weizero Tsedale Wolde Tekle.

**

Alexander "Skunder" Boghossian was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1937.

When he was a child, his parents took seriously his talent and encouraged him to become an artist.

In 1954 when he was seventeen years old, Boghossian won second prize at the Jubilee Anniversary Celebration of Emperor Haile Selassie I. The next year he was awarded an Ethiopian government scholarship to study in Europe. He spent two years in London where he attended St. Martins School, Central School and the Slade School of Fine Art. He extended his sojourn in Europe another nine years as a student and teacher at the Academie de la Grnade Chaumiere in Paris, and as a student and teacher in the atelier of Alberto Giacometti.

In 1966 Boghossian returned to Ethiopia where he taught at the Fine Arts School in Addis Ababa until 1969. He made his first trip to the United States in 1970 and, except for a trip home when his father died in 1972, he spent the remainer of his life in the US. The 1974 revolution in Ethiopia prevented Boghossian from returning to Ethiopia. He has lived in the USA as a permanent resident, and artist in exile.

Throughout his career Boghossian has had a successful dual profession as an art instructor and artist.

In addition to teaching in France and Ethiopia, Boghossian has taught in the USA at Atlanta University, Hampton University, and Howard University, where he worked in the School of Fine Arts since 1974.

As a practicing artist, Boghossian's paintings have been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Ethiopia, the Caribbean, Europe, North and South America. He is also distinguished by being "the first Africa to..." He was, for example, the first contemporary African artist to have work purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and he was the first African commissioned by the World Federation of the United Nations Association to design a First Day Cover for a United Nations stamp. His pen and ink drawing for the cover and the accompanying stamp were on the theme of "Combat Racism." The date of issue was September 19, 1977.

**

This page is dedicated to the life and times of the greatest modern Ethiopian artist, Alexander Skunder Boghossian.

Boghossian was born on July 22, 1937 in Addis Ababa, at the time the capital of the Italian colony Italian East Africa, one and half years after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. His mother, Weizero Tsedale Wolde Tekle, was Ethiopian. His father, Kosrof Gorgorios Boghossian, was a colonel in the Kebur Zabagna (Imperial Bodyguard) and of Armenian descent. Kosrof's father, Gregorios Boghassian, an Armenian trader, had established a friendship with Emperor Menelik II and worked as an traveling ambassador in Europe on behalf of the Emperor.

Boghossian's father was active in the resistance against the Italian occupation and was imprisoned for several years when Boghossian was a young child. His mother had set up a new life apart her children and although both he and his sister Aster (Esther) visited their mother frequently, they were raised in the home of their father's brother Kathig Boghassian. Kathig, who was serving as the Assistant Minister of Agriculture, together with other uncles and aunts brought them up during their father's imprisonment.

He attended a traditional Kes Timhert Betoch kindergarten where he was taught the Ge'ez script. In primary and secondary school, he was taught by both Ethiopian and foreign tutors and become fluent in Amharic, English, Armenian and French. He studied art informally at the Teferi Mekonnen School. He also studied under Stanislas Chojnacki, a historian of Ethiopian art and watercolor painter.

Boghossian won second prize at the Jubilee Anniversary Celebration of Haile Selassie I in 1954. The next year he was granted a scholarship which allowed him to study in Europe. He spent two years in London, working at St. Martin's School, the Central School, and the Slade School. He then spent nine years studying and teaching at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. In 1966 he returned home, teaching at Addis Ababa's School of Fine Arts until 1969. In 1970 he emigrated to the United States, teaching at Howard University from 1972 until 2001.

Boghossian was the first contemporary African artist to have his work purchased by the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1963 and the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965.

In 1977, he became the first African to design a First Day Cover for a United Nations stamp. He was commissioned by the World Federation of United Nations Associations. His pen and ink drawing on the theme of "Combat Racism" for the cover and the accompanying stamp were issued on September 19, 1977.

In 2001, Boghossian worked with Kebedech Tekleab on a commission called Nexus for the Wall of Representation at the Embassy of Ethiopia in Washington, D.C. The work is an aluminum relief sculpture (365 x 1585 cm) mounted on the granite wall of the embassy. Nexus includes decorative motifs, patterns and symbols from Ethiopian religious traditions including Christianity, Judaism, Islam and other indigenous spiritual practices incorporating symbolic scrolls and forms representing musical instruments, utilitarian tools, and regional flora and fauna.

His work is held in a number of permanent collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC.

Boghossian is represented in New York by the Contemporary African Art Gallery.

Alexander (Skunder) Boghossian: A Jewel of A Painter of the 21st Century

(Prepared for the African Arts Council 12th Triennial Conference Hosted by Dubois African American Studies Institute at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA March 31, through April 3/04)

by Achamyeleh Debela , Professor of Art, Department of Art, North Carolina Central University

Alexander Skunder Boghassian's life started in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 1937. He was born one year after the invasion of Ethiopia by fascist Italy, a historic time that will forever be remembered in the annals of history of the Ethiopian people. The reason being that the invading Italian fascists under the leadership and instigator Benito Mussolini deliberately decimated a generation of Ethiopian intellectuals, and massacred millions of Ethiopians using nerve gas. The Ethiopian holocaust of bombing and poison-gas raids took place in daylight as the world body, the then League of Nations debated dispassionately on the fascist aggression in 1935-6. This holocaust was perpetrated upon Ethiopian people so as to facilitate Italy's colonial ambitions of enslaving the people and expansion. Nevertheless, modern educational institutions that combined elementary and secondary schools, including military schools among other modern infrastructures, had begun prior to 1935 initially during the reign of Emperor Menelik II. The introduction of Modern education was thought an essential ingredient by the Ethiopian government and the Emperor Menelik II School was established by Menelik in 1908.

The Teferi Mekonnen School was later established in 1925 and numerous others had begun to provide requisite education in the various provinces. These institutions produced more than two hundred of the intellectuals who were instrumental in the administration of the Ethiopian government prior to 1935.

The presence of foreigners in Ethiopia as travelers, traders, missionaries, and as members of expedition groups has been documented extensively. But an account of a particular group or in this case a family from Armenia becomes instructive. To give a brief background of one of Ethiopia's brilliant creative artists and a jewel of a painter of the 21st Century it is important to share aspects of his background and the story of his life and, where appropriate, his time. Accordingly we learn about an Armenian Trader who in the late 18th century began his journey from Constantinople and traveled via Aden to Djibouti and using local camel caravan arrives at the court of Emperor Menelik II. Soon after he establishes a friendship that would later make him an itinerant Ambassador to various parts of Europe on behalf of the Emperor. This entrepreneurial itinerant ambassador was none other than Gregorios Boghassian, grandfather of the artist Skunder Boghassian.

Since antiquity Ethiopians have been known for their hospitality. Through ancient Greek literature we learn that it is the place where the Gods came to rest and recoup. We are also told that the prophet Mohammad had advised his followers to seek shelter among the Ethiopians to avoid persecution. Ethiopia has served as a land of peace and a place of security and adventure. This is further illustrated by survivors from the Beta Israel who were lost and navigated their way to Gondar. Armenians, Greeks, Italians, British and others have been known to come in peace, sometimes with a hidden agenda in mind and sometimes without. Most were treated with love and respect until the real nature of their loyalties and mission were recognized for what they were: colonial ambitions. In view of the above we focus in this paper on a specific family who not only adopted Ethiopia as their home, but also fought to insure its continued independence and substantially contributed in its attempt to survive and develop in its own way.

The Ethiopian Historian Bahiru Zewde writes that:

"The Armenians who were orthodox Christians like the Greeks and welcomed to Ethiopia at a time when they were suffering from persecution in their homeland, were to attain the highest level of integration into Ethiopian society. They thrived mainly as craftsmen catering to the upper classes. But one of their pioneers Sarkis Terzian made his fortune as arms trader and his fame by introducing the steamroller. (Aptly named 'Sarkis Babur, the steam engine of Sarkis, into the country.)" (Zewde, 1991)

Skunder was a mere infant, a one-year-old baby when his dad left to join the Ethiopian army to fight the Fascist invaders. The colonel was captured by the Italian army while returning after seeing Emperor Haile Selassie off to exile. The colonel and other Ethiopian patriots who served at the highest level for the Ethiopian regime were dangerous to the occupying Fascists because they were thought to be organizing a resistance. Hence, they were hunted down and arrested. They were taken to an Island in the Italian peninsula, possibly at the infamous Corsica prison. Among those imprisoned at the time were the Emperor's cousin Ras Emiru Haile Sellassie, the well known Author Haddis Alemayehou, Minister and Author Girmachew Tekle Hawariat, Engineer Abebe Gabre Tsadik, to name a few. Suffice it to say Skunder did not see his father until he was seven.

Skunder's mother Weizero Tsedale Wolde Tekle had set up a new life apart from the two children. In the interim Skunder and his sister Aster (Esther) Boghassian visited their mother frequently but were reared in the home of their father's brother Kathig Boghassian, who was serving at the time as the Assistant Minister of Agriculture. For all practical purposes all the Uncles and Aunts who stayed behind to take care of the many children and extended family for the duration of the seven years of the colonel's imprisonment brought them up. Skunder's father was highly regarded as an expert horseman and served in a capacity where he was in-charge of all matters regarding the royal stable and the special guard assigned to it. He also organized the Equestrian Group Guard Polo Club, which participated with the Greek, Italian and British Polo Clubs in competition at the Jannhoy Meda on weekends. As a father he was strict and took the position of the old school of parenting which was decidedly protectionist. Skunder grew up in Addis Ababa, near Nazret School or near the Church of St.Mary, or to be more accurate by Feres Bet. According to his sister Aster Boghassian from the beginning he was precocious and curious and began to draw very early.

"I fondly recall him as a cheerful and mischievous little boy and, much adored by all members of the family. He started drawing at an early age. I should say the moment he was able to hold a pencil. He was an inquisitive child who tried to discover everything by himself. He could imitate and mimic different accents and gestures that made people laugh. He had a great sense of humor. He had a personality that drew many people who admired his outgoing nature As a young man he liked playing soccer and tennis. He enjoyed going hunting (like all our young male cousins) with an uncle (a great hunter himself) and our father. But, to our father’s disappointment neither Skunder nor I had that passion to be good horseman/woman like him".

Dr. Fikru Boghossian, a cousin of Skunder, said this about Skunder: "Skunder as a young man was athletic, outgoing, jolly and at times clownish and yet curious and always inquisitive." Skunder drew and painted every chance he got and made copies of subjects from the Orthodox church, his favorite being St. George killing the Dragon. In fact it was one such copy that he shared with his early mentor, one Jacques Godbout whom he gives credit as his first true teacher and critic in art. He met Jacques Godbout who was at the time teaching mathematics at the then University College in Addis Ababa. Jacques Godbout was a Canadian philosopher and painter who later became a filmmaker in Canada. He also sat on the Canadian Film Board. Jacques recognized Skunder's talent and took him under his wings as an apprentice.

At the age of sixteen Skunder visited Harrar and was fascinated and inspired by the discovery of the culture, costumes, jewelry and varied women in the market. As a result of this visit Skunder did a series of paintings and sketches fin water colour and ink. In 1955 Skunder participated in a national exhibition, which was part of the celebration of the 25th Anniversary of Emperor Haile Selassie's Coronation silver jubilee. He would win the second prize and Emperor Haile Selassie would ask him what he wanted. The immediate response was that he be given the opportunity to study in England. The first prize went to Ato Mekbib Gebeyehou who later become the Charge D' affair of the Ethiopian Embassy in Washington D.C. Mekbib who laments to this day that Skunder actually received the scholarship that he should he should have gotten. Currently Mekbib is a professor at the University of the District of Columbia in Washington D.C. Destiny rather than Skunder made the determination of both gentelmen's fate.

Skunder and his Experience in Europe

Paris during the late 50's and early 60's was a meeting place of diverse intellectual trends and it provided Skunder with a vigorous experience and shaped his personal philosophy and artistic style.

In 1955 Skunder arrived in London and immediately enrolled in St. Martins School. Shortly after he went to the Slade School of Fine Arts and later the Central School. Skunder had a quick and firm grasp of foundation level courses such as concepts in design, composition and anatomy, and an inherently high skill level. Thus, the academic nature of the instruction was less appealing to him. He later would say that, "At the time all I wanted to know was the craft." He was getting restless as he wanted to venture into studio and practical experiences. Skunder needed an environment that would feed and nurture his hunger for creative inspiration and motivation and apparently London was not providing that atmosphere. In 1956 he participated in a group show at the London Contemporary Arts Society in the foyer of a cinema on Church Street, Enfield. Interestingly a reporter who covered the exhibition observed, " His "Ballet" was one of three pictures he had accepted for an exhibition at Addis Ababa to mark the silver jubilee of Emperor Haile Sellassie." He further observed that " The room which "Alex" occupies in Fellow Road, Hampstead, is filled with pictures which cover an astonishingly wide range." The reporter was also impressed with specifically his studies of animals and writes, " some of his wild animal studies are magnificent" I found Skunder's response to this observation rather telling of how he felt in the first two years or less away from home. Skunder responded, " But I paint things like that when I feel homesick and start thinking about Abyssinia".

Skunder at this time had apparently reached the conclusion that he would travel to Paris, France. Professors and some of his West African artist friends, mainly Nigerians and Ghanaians that he met in London, also believed that the Parisian environment was indispensable to continued growth. Convinced of the different possibilities potentially available in Paris, he made the decision to go there for the summer. Paris at that particular juncture was the mecca of artists of all persuasions. On his first trip to Paris Skunder stayed at the Armenian House of the Cite Universitaire. While there he visited museums, artists studios and the art schools. A two months stay would convince him that Paris was where he needed to be. The difficulty, however, was that he did not have a scholarship for Paris, nor did he have the financial means to stay on his own. He then decided to write and ask the Emperor's permission to continue his studies in Paris. He wrote, "after I have done two visits to Paris and met the leading painters there, I wrote to H.I.Majesty (Emperor Haile Selassie) for permission to continue my research in Paris, which was granted. I was highly encouraged by H.I. Majesty. He owns ten of my paintings in his big collection and has helped me very much." Soon Skunder's wishes came true, he received word that he could continue his research in Paris. In Paris his first act was to register at the Ecole Nationale Superiore des Beaux Arts. Here, he enrolled in the mural painting class under the supervision and guidance of professor Gardin. However, Skunder found life outside the school to be a more interesting and challenging place to be. He began hanging out in the Cafés of Montmartre and visiting museums and artist's studios when and where he could. Between 1957 and 1960 his exposure to the arts activities in Paris became what the Parisian critic Compte Philippe D'Arschot described as, "Today (Skunder) hopes not to interrupt his studies and to keep active that vital and creative glow that he finds beyond himself in the Parisian climate which unceasingly nourishes the Arts." While absorbing the craft of mural painting and other classes he was taking under his teachers at L' Ecole d'Beaux Arts he was also absorbing and observing what was happening daily around him. For the first time he met artists of color from Brazil, Cuba, Kenya, the Sudan, South Africa and the USA. He said, " I had no concept of any black people other than the Nigerian and Ghannian in London." Here was a moment that made a difference in his young exiting life. He was suddenly in the middle of the Negritude movement where African intellectuals were vitalizing and articulating via publications such as Presence Africaine. Here was a newly established publishing house where the likes of Aime Cesaire and Leopold Senghor frequented. This was one of the places where Skunder was hanging-out, the place for all practical purposes where the school out side of school becomes a reality. Here he met many of the intellectuals and in an interview for Third-Text Skunder recalled, * "My French started to improve, and I got to meet big guys like Aime Cesaire and Leopold Senghor". This indeed paid off when in 1959 Skunder was one of three artists selected to attend the second Congress of Negro Artists and writers held in Rome. It had been only 4 years since he left Ethiopia at 17 and he was now only 21 years of age. It is possible that he may not have understood the significance of this important gathering, but nevertheless he felt enormously proud of his selection. It meant that Skunder was to exhibit with artists such as Jan Gerard Sokoto, a prominent South African artist who was living in Paris and one Tiberio from Brazil, a devout socialist, and Ibrahim Papa-Taal who later became a prominent artist from Senegal who was also studying at L' Ecole d' Beaux Arts. At this time Skunder began to really struggle and experiment with ideas of how to find ways and means of expressing the multiplicity of cultural currents that were now converging in this new milieu. In his mind he has to mix and sift what these cultural currents mean and identify the intersection and attendant manifestation. What would it mean and what would it bring to Skunder? How would he respond to this phenomenon? One can only imagine the atmosphere of Montmarte during this period where all cultures and backgrounds are converging and manifesting themselves daily via artists, critics, art historians, writers, politicians, poets and philosophers. Skunder recalls, "One could make a definition for oneself, the world, and the universe right there in Paris. You had the brightest minds from Africa and the Diaspora at the time. There they came together and talked for the first time about their various experiences. It was a vehicle for the negritude movement." Skunder then and there decided that he would learn about not only the movement, but also its cultural and spiritual source. He gives credit to Merton Simpson who introduced him to Madame Madeleine Rousseux, a collector of classical African art who lived behind Notre Dame in the Latin Quarter. Madam Rousseux, according to Skunder taught him " the concept of the vital force and Dogon Cosmic religion". This was also an introduction to West African religion and art particularly that of the Dogon Cosmology. In addition to learning about the aforementioned he was also exposed to the concepts of Aime Cesaire's poetry and Senghor's idea regarding "negritude". The negritude in this instance that signifies attempts to maintain a positive racial identity. Here Skunder fused the two ideas of negritude and surrealism and brought about a new dimension of expression in his paintings. Surrealism is defined as "a modern movement in art and literature in which an attempt is made to portray or interpret the workings of the unconscious mind as manifested in dreams; it is characterized by an irrational, fantastic, arrangement of materials". It took a few years but Skunder found a new aproach in painting in his interpretation of this cultural intersection. Through experimentation he had come up with some dynamics in the use of images dealing with symbols, colors and textures. Between 1960 and 1965 Skunder worked continuously to find a style of his own. Concocting ideas and conjuring images and the world of surface textures to announce their presence were more than a technique that Skunder has discovered. He had internalized way back then when he was fifteen being tutored by Goudbet. Goudbet had introduced him to the various types of art movements and paintings through books. Skunder had a good idea of what the Impressionists, Post Impressionists and or the German Expressionists were about and he was then told that if he wants to be a painter he needed to understand that universe. Skunder talked about this particular exchange and sums it up as a challenge and said, " He (Goudbet) was trying to liberate me, introduce me to new things. He for an example asked me to paint St. George and the Dragon, a popular Ethiopian theme, but he did not want me to paint the dragon as a dragon, the horse as a horse, or St. George as St. George. I said, what do you mean, not paint St. George or the horse? . He was teaching me intuitiveness, that anything goes provided you think of a horse in the back of your mind." This lesson of seeing beyond the surface and internalizing concepts and projecting them within and without and discovering nuances and allowing them to exist becomes the modus operandi of Skunder's new discovery of style and form of expression for a long time to come.

In 1960 Skunder met Merton Simpson, an African American painter, collector and gallery owner who apparently frequented Paris and visited friends who were into Jazz and other artistic performances. Skunder admired Merton's broad knowledge of traditional African art, his love of music, and his willingness to help others, infact he considered him a renaisance man. Skunder became a good friend. Skunder was introduced to Merton Simpson through the Harmon Foundation, an organization established by the philanthropist William Elmer Harmon, located in New York to promote the arts and artists of color including those in Africa. * The Harmon Foundation through two of its employees, Mrs Evelyn Brown, assistant Director and Miss Mary Beatle Brrady, Director used correspondence as a way of assisting many contemporary African artists with fellowships, arranging exhibitions, and providing information on possible contacts in the USA. Mrs. Brown who was compiling information along with a Dr. Washington about contemporary African art for a book contacted the Ethiopian consulate in Paris to get information on Ethiopian artists and arts activities. She did not recieve a response, but later learned of Skunder through a Sierra Leonian performing artist named Miranda Burney-Nicol and contacted Skunder via a letter dated October 16, 1960. Having now heard about the Harmon Foundation Skunder corrosponded with Mrs. Brown and began a very long relationship which lasted untill the Foundation was closed. His first request from the Foundation was for assistance in finding venues for exhibitions. This was followed by inquries about possible sposorship for residenies in New York where the Foundation was located as well as any other place in America.

Skunder was now independently trying to suport himself as he no longer recieved assistance from the Ethiopian government. Skunder was told by Mrs. Brown of the Harmon Foundation that he would be included in the revised edition of the book titled Contemporary African Art and that the Foundation planned to purchase two peices of work from each artist included in the book. Further, he wouldl be included in an all African exhibition that the foundation planned to organize. Skunder was also advised that it would be possible to have a one person show provided he had enough work.

Skunder at the Chateau Ravenel (Oise)

By October of 1961 Skunder applied to work in a studio at a castle fifty miles south of Paris. This is where serious young artists when selected were given a studio and an oportunity to produce a body of work. Skunder was selected to work in the castle which was located in the south of France. Excited he wrote to the Evelyn Brown of theHarmon Foundation:

“My Dear Miss Brown

After fifteen days of moving up and down, I finally settled down, in a beautiful place, right in the elite of the French Young school, among Llaffitte,Manessier, Andre, Moon. They gave me a studio, & the working possibilities, ever since five days I work like a mad man.....already three canvasses half way through a huge stone that I am carving....& plenty Drawings. As soon as I judge some work worthy of an exhibit I will send you."

He goes on explaining how his new environment is isolated from civilization which meant no hanging around at the caffes of Montmartre for inspiration. The new change introduces nature and coble stoned walls and taking care of a number of hens & chickens and an occassional early morning horse ride. The enthusiasm of life in the Chateau was a wonderful experience that gave Skunder a new energy and the determination to being productive. However, without the scholarship and no other source of income Skunder was having difficulty staying in the castle. Hence he writes, “ I am feeding on milk and potatoes for the last month, honestly its no fun. I had bought material to work with for a month, this actually keeps me going, I have managed with all this inconvenience to provide 3 good paintings out of 6. There again I can not afford to send them or mail them to you. Would you accept if I mail you C.O.D? if yes please write to me, they would fit in with the rest for the show....." He now contemplates going back to Paris. He complains about the heat in his appartment not working and how very cold it is and how he was forced to sleep with his clothes on. In addition, he was not eating well. It was at this juncture that he received an offer by a Mr. Jean Calliens of the Presence Africaine to participate at the Festival of the Negro Art which was to be held in Dakar in the Spring. In November of 1961 Presence Africane asked Skunder to decorate the cellar of the publishing establishment.

From Paris to Madison Avenue and back to Paris

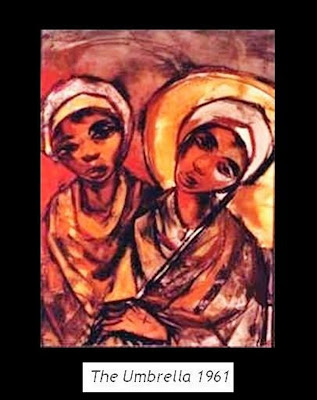

By June 1961, Skunder had sent to the Harmon Foundation in New York nearly 53 paintings and by December they were on exhibit with the exhibition list titled: "Alexander Boghssian: A selection of Oil and Watercolor Paintings on Life in Ethiopia". The majority of the painings at the Madison Avenue Merton Simpson Gallery exhibition were figurative works and Skunder was asked to comment on each painting. For example, in a painting titled Young Girl Seated, he would write, " I like to think of this as a combination of poetic thought that was prompted by the image of my mother".

Prior to returning to Paris Merton Simpson arranged a meeting with some of the major African America artists such as Jacob Lawrence and the Spiral Group. Those African-American Artists he claimed were his big brothers and his American mentors. Skunder visited New york in June for his first one man show and returned in September to Paris.

From the Expressions of Klee, to the Expression of Africa via Roberto Mata, Ibrahim El Salahi, Gerard Sokoto and Wilfredo Lam

For the next few years Skunder was engaged in a deep search of finding a stylistic direction. He worked with a new vision and new approach. He encountered the art works of Klee and was suddenly mesmerised at the resolution and complexity and yet found the mystery brought together in a sophisticated simplicity. Skunder absorbed his findings and came up with a solution. That solution was to liberate himself from Klee, a lesson well learned from Goudbet in 1955-1956. To Skunder what was important was how he found himself in the center of a cultural explosion and how he made use of the experience for a new visual vocabulary. He talked about his findings in nature and how he extended that symbolically as a departure. Skunder had contained his experiences abroad, his encounters with Africans from Africa, the Islands, from North and South America until he found a way to release it with a medium, a style and a form. His travels between the continents and the personalities he encountered have definitely nourished his visual and artistic sensibilities.

" I was heavly influenced by Cesaire. His imagery, the graphicness [sic] of it, was puncturing. I was a surrealist and he formed for me a stronger vision. He introduced me to more surrealism in poetry. He made me read Edouard and Appolinaire. Cubism became clearer to me in its departure of thought, its ideas and mannerisms. I could feel it, but I did not know how to do it. I did not know how to translate the idea. I had wresteled with this in Ethiopia, with Goudbet."

Skunder had visits to his studio in Paris by Roberto Matta, the renowned Chilean surrealist. Having seen Skunder’s new works Matta encouraged him and promised to come to his studio from time to time to see the progress in his work.

Energized by this encounter with the seminal surrealist Roberto Matta, Skunder writes Ms. Brown of the Harlem Foundation to whom he has sent several of his new works: "Matta the famous Mexican painter has encouraged me very much and he says he will be coming from time to time to see the evolution. Previous to Matta's visit Skunder had seen the work of the Cuban Artist Wilfredo Lam. This proved to be a watershed in Skunder's artistic and intellectual inquiry by awake-ning a different energy that culminated in a synthesis of many cultures, but the Pan-Africanist dimension was at the core. A connection had been made that sparked a light in Skunder and became an umbilical cord that fed the creative womb with a new language to which Skunder developed symbolic alphabets. In explaining the importance of the encounter with Wiilfredo Lam's single drawing in London and later, of Lam's works in a solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Skunder would say, " Each artist goes through a journey of learning how to articulate what is inside of him. For me, it was this pointedness ( of Wilfredos as well as Matta's works) and for others it could be volume of color.

It could be emotions, feelings, graphic renderings of nature, or organic images. ...if there was an artist that I would say that I was influenced by, it would be Wilfredo Lam." The strength of influence by any one of the artists mentioned here may or may not graphically be seen but the source and influence of the artists experiential landscape and references to individual pictorial dialogue and synthesis is enormously diverse.

Gerard Sokoto introduced Skunder to Wilfredo Lam and we can only imagine the exuberance felt by Skunder who totally idenified and loved Lam's work. Additionally, the author of the single drawing in London was insignificant. What mattered was the work itself. For example, Skunder made an interesting observation of synthesis and analysis and the resultant objectification. Having acknowleged the kind of influence that Klee, Matta and Lam may have had on his own way of painting and the reason for it he concludes that, "Latin-American artists have brought to me the same functioning agony. It is through them that I have found a closeness to the continent. Latin America became a synthesis of Europe, Africa, and America. What was synthesized was immediate to us as Africans, more so than Picasso or Giacometti. They (Picasso & Giacommetti) were discovering Africa on another level".

Every thing Skunder experienced in life is engaged in the creative process. In otherwords he begins a painting and until he finishes that paining it is a process of visiting and revisiting, shaping and reshaping. He said, " some paintings are ideas, others are experiences or imagined landscapes from actual experiences. Some paintings are recurring images and themes. Paintings are also social recurrences and political philosophies. They are all parts of the life I have lived, am living, or am surrounded by. While I am working my state of mind either accepts or rejects them for its own comfort. Once it is setled in that comfort, it continues to rediscover, invent or re invent those experiences." This statement is crucial to understanding the works of Skunder and indispensable to making an analysis of the technical dexterity and sophistication of his synthesis and hidden references.

Skunder has come to terms with himself and made a deliberate decision to deal with human preoccupation and human concerns. " I try to get involved with the inner mechanisms without altering the feelings, the premordial feelings" he said.

The so called premordial feelings are actually those feelings that make him want to paint. To Skunder the process of painting is more engaging and far more important than the finished product. He explained, " Where I want to go is actually more fun for me because the finished product, most of the time, I am not happy with." No one can explain this process better than Skunder himself. Habitually, Skunder paints with music in the background, particularly Jazz music. Though earlier in his encounter with Cesaire he was influenced by literature, poetry helped him conjure imagery but music was a companion in his journey through the creative process of painting. After all Skunder began to listen to Jazz music when he was seven years old, from a radio broadcast which at the time was relayed from Morocco. Since then it seemed Skunder was constantly listening to Jazz. Skunder would say about music simply, " It is another force. It is a companion."

In 1964 Skunder returned to America and was married to an African-American from Tuskegee, Alabama. He met his lovely wife while in Paris. A year later she was expecting and they decided to have the baby in Ethiopia. Hence, Skunder returned home for the first time since his 1955 scholarship to London.

Skunder had been working very hard while in Tuskegee. These works coupled with other works brought from Paris were left with the Harmon Foundation. He had no other job and and he needed money to take his wife to Ethiopia. He borrowed money from the Foundation which he later repaid from the sale of works. The lack of business acumen and a preocupation with producing the next painting may have contributed to the devaluation of Skunder's work. A case that comes immediately to mind is the recent acquisition of Night Flight of Dread and Delight by the North Carolina Museum of Art. In 1998, just five years before his untimely death, the museum paid $35,000.00 USD for the work. Ironically, this sum represented the largest paid to date for a work by Skunder. The initial purchase price of the work was a mere $1,200, of which Skunder received $800.00.

Skunder returned to his beloved Ethiopia in 1966, and for the next three years taught at the Addis Ababa School of Fine Arts. His studio located within the school attracted more students than any other studio on campus. The impact on the younger generation of Ethiopian artists was a lasting one. In particular Tewodros Tsige Markos, presently in Paris, Enadale Haile Sellassie, deceased and Zeryihun Yetimgeta worked directly out of his studio. Many other students were similarly enamored by his work as well as his personality. His influence was so strong that for a while it was difficult to distinguish between his work and that of his students. Today one can still see Skunder's visual vocabulary in the work of both older and emerging artists. These artists mimic Skunder's style without the benefit of his varied experiences and merely attempt a superficial technical presence. In spite of his short stay between 1966 to 1969 he took Addis by storm. He traveled to the historic sites and studied the ancient architecture of the rockhewn churches at Lalibela and the monuments at Aksum, the wall paintings and icons, crosses, and the magic scrolls while carefully making notes and sketches. Skunder maintained a frenetic pace, painting while teaching classes during the day and painting at night while not attending foreign embassy parties. The one constant was that he placed a premium on the importance of creative productivity. Skunder was a cause celebre; indeed he was celebrated throughout the Horn of Africa. He was a winner of the 1966 Haile Sellassie I Prize, the highest award for Fine Arts in Ethiopia. The prize included a gold medallion, certificate and a $7,500 monetary award. Both Skunder and his wife Fanu were the toast of the town. They were invited several times each month to gala affairs for ambassadors and visiting foreign dignitaries. Skunder commented, " We were on the list of protocol. During the week we were sampling foods from other African countries, France, America and Trinidad. Socially we were burned out".

At the height of the feverish analysis of "Modern Art" in Europe and North America, and long before it became fashionable to make art history out of "Traditional" based African Art, Skunder was producing his seminal works the Nourishers series of paintings in Paris. He was in the middle of the liberation and Pan-African discourse at a historic junction in early 1960s Paris. He was at that time truly Modern with an ancient, traditional, yet contemporary accent. When it was believed that all that Africa had to offer was "Tribal" art forms, Skunder's works were hanging in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Modern Art Museum in Paris. Indeed this was loud and clear testimony to the talent and artistic genius of this son of Africa that hailed from the cradle of humanity, mother Ethiopia. His was a mission with a passion and a pioneering journey that evolved into a long expedition into his Ethiopian past with a kindred, creative spirit.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Skunder Boghossian, 65, Artist Who Bridged Africa and West

By HOLLAND COTTER

Published: May 18, 2003, Obituaries in New York Times

Skunder Boghossian, an Ethiopian-born artist who played an important role in introducing European modernist styles into Africa and who, as a longtime resident of the United States, became one of the best-known African modern artists in the West, died on May 4 at Howard University Hospital in Washington. He was 65.

No cause of death was released, but he had been ill for some time and was found unconscious in his apartment, said Kimberly Mayfield, a spokeswoman for the National Museum of African Art in Washington.

Mr. Boghossian, whose original first name was Alexander and who used the name Skunder professionally, was born in Addis Ababa in 1937. In 1955, on a scholarship from the Ethiopian government, he enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, and two years later moved to Paris, where he taught at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. In Paris, he became associated with the Senegalese philosopher Cheikh Anta Diop and other figures in the Pan-African and negritude movements. His art combined European media like oil paint, crayon and ink with bark and animal skins. Often hallucinatory in quality and filled with intricately detailed figures and patterning, his work was influenced by Paul Klee, Max Ernst and the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, but more strongly by Coptic and West African art.

In 1966, he returned to Ethiopia to teach at the School of Fine Arts in Addis Ababa. He stayed only three years, but his presence helped revolutionize contemporary art in the country. In 1969 he moved to the United States, where he became artist in residence at Atlanta University and instructor at the Atlanta Center for Black Art. He taught painting at Howard University from 1974 through 2000. Several of his Ethiopian students, including Zerihun Yetmgeta, Wosene Worke Kosrof and Tesfaye Tessema, followed him to America. His influence in Ethiopia itself remained strong.

Mr. Boghossian was the first contemporary Ethiopian artist whose work was bought by both the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris (1963) and the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1965). The National Museum of African Art in Washington owns several of his paintings. A few of them are included in the group exhibition ''Ethiopian Passages: Dialogues in the Diaspora,'' on view at the museum through Oct. 5. He is represented in New York by the Contemporary African Art Gallery.

Mr. Boghossian is survived by a daughter, Aida, of Jessup, Md.; a son, Edward, of Bloomington, Minn.; and a sister, Aster, of New York City.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий